Harry Smith

In 1960, when Bob Dylan was living in Minneapolis (he went by Zimmerman in those days), he had a friend named Paul Nelson, who at the time had an amazing record collection. One weekend when Paul was out of town, Bob decided to “liberate” about 25 of Paul’s records. In Martin Scorsese’s documentary film No Direction Home, Bob explains his reasoning for this: "He (Paul) had a whole lot of records which probably couldn't be found anywhere else in the Midwest, so I helped myself to a bunch." And since Bob saw himself as a "musical expeditionary”, you know, a genius, well… anyway it all worked out.

Among the records that Bob Dylan was said to have acquired that day was The Anthology of American Folk Music - also known as The Harry Smith Collection. And on that weekend Dylan had not only acquired the records themselves, but a vast treasure trove of the music and lyrics that he was able to absorb and make his own. It wasn’t stealing, but it was an enormous influence. Dylan wasn’t alone in this, The Anthology of American Folk Music influenced his whole generation and brought traditional American folk music out of the past and into the here and now (or the there and then anyway).

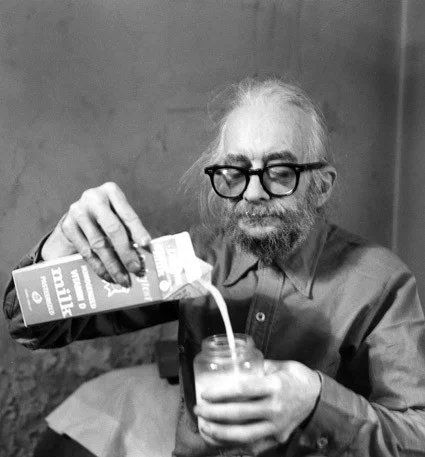

The Anthology of American Folk Music was the brainchild of Harry Smith, a lifelong bohemian and eccentric as well as a painter, a writer, an experimental filmmaker, an anthropologist, linguist, vagrant, and general oddball. He was also a collector and a hoarder. He collected many things: paper airplanes, Ukrainian Easter eggs, string figures, and most of all records. The Anthology of American Folk Music was made up of Smith’s collection of old recordings of “hillbilly”, Cajun and blues performers that were long out of print. He found them in junkshops, flea markets, and used record stores all over the Northwest. These records were not field recordings, but commercial products meant to make a little money by tapping into rural, working-class markets – under-served communities that the big labels couldn’t be bothered with.

In 1947, desperate for money, Smith sought out Moe Asch, the head of Folkways Records. Asch, another eccentric, was Folkways’ founder, director, and sole proprietor for almost 40 years. He had no investors, no stockholders, and just a handful of employees. He also had no interest in being told what to record or release, or for that matter, what was profitable, what was authentic, or anything else. Folkways, despite being a supposed for-profit business, took an approach that more resembled a non-profit archive. Two-thirds of Folkways recordings sold less than 100 copies and the most of the rest never broke 500. Yet nothing ever went out of print, Asch reportedly said, "Just because the letter J is less popular than the letter S, you don't take it out of the dictionary”. He was able to do this by paying no royalties whatsoever unless forced to, and yet somehow he remained beloved. Folk singer Dave Van Ronk once said of him: "Moe Asch could be an exasperating man, and he would never pay you ten cents if he could get away with five, but he really loved the music."

So, Asch and Smith were a perfect duo, and Asch decided that instead of just buying Smith’s records he would recruit him to oversee the whole project. It was a win-win: Asch would bring a rare collection of recordings into his catalogue, and Smith would come to see his vision of music, art, anthropology, and esoteric spirituality achieved. Neither seemed to worry about the legal issues, let alone sales.

Smith was given complete freedom in overseeing the project. He designed the covers (each representing the alchemical elements of water, fire & air) and the booklet, did all the post-modern collage artwork, decided on song sequences, and wrote the liner notes. He even wrote up a series of brief, out-there song descriptions (e.g. for "King Kong Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O" by Chubby Parker, a song about a mouse marrying a frog, Smith’s notes state: "Zoologic Miscegeny Achieved in Frog-Mouse Nuptials, Relatives Approve.")

The Anthology entered the market at the perfect time. When it was released in 1952, the music business was booming in the post-war era. Small labels and “race records” were selling like mad to an earnest and hungry audience, and America was at the pinnacle of its elusive search for the “pure and the authentic”. This trend had started a generation earlier with Alan Lomax’s field recordings, and led to the folk music revival, which was just beginning. The irony was that the performers on The Anthology of American Folk Music were not playing music of their own time, but rather music of a bygone age that was meant to elicit nostalgia and hopefully sell records. The authenticity-seekers may not have caught this irony.

Smith went on to become major cult figure in the 1960s, producing the rock band The Fugs, writing and performing his own songs with Allen Ginsberg, being named “Shaman in Residence” at the Naropa Institute, and topping it off by living (and eventually dying) at the Chelsea Hotel. Meanwhile his record collection’s influence spread across America, beyond the rural south and into the mainstream, up North and even Britain. Every element of The Anthology of American Folk Music - from the songs, to the song sequence, to the artwork - found its way into our psyche, and its musical influence can be heard in American music from The Band to Springsteen and more recently Jack White, Wilco, and alt-country in general.

Read More